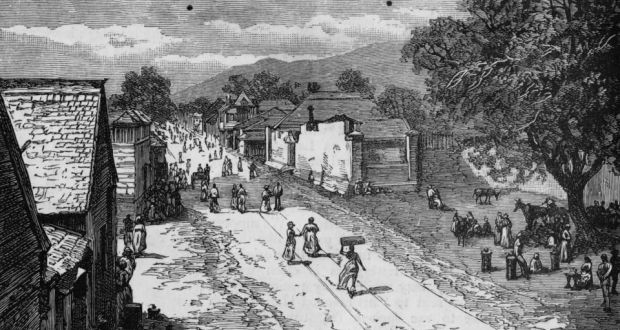

King Street in Kingston, Jamaica, circa 1800. (Photo by Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

In the mid-1990s I attended a St Patrick’s Day party in Israel where most of us were Scottish, Welsh and Irish. A man from Jamaica joined our crew. He sang along to the Irish songs and even had his own version of the song, The Wearing of the Green. I assumed the Jamaican liked Irish folk music or had spent some time in Ireland. He told me he’d never been to Ireland. However, he identified his heritage as Irish.

Most of us born in Ireland pre-1990 will have attended a Catholic school, sat beside a white Irish child, taken a white boy or girl to our debs and had little to no interaction with people other than Irish, Catholic and white. As a “blow-in†to the rural town I was as foreign as it got.

At that age I could tell from certain surnames where their family originated. In my home country, families with surnames Ryans, Dwyers and Elys can trace their ancestry back 1,000 years. Knowing at least that much, I looked at the Jamaican and noticed the obvious. He didn’t look like the Ryans or Dwyers I knew, and most notably he did not look like he’d any Irish heritage.

I must have appeared doubtful but he went on to tell me his father’s family were Irish. The story that was passed down the generations was that his great-great grandfather came to Jamaica in the 1850s from Waterford. I remained doubtful, and without google or smartphones in the 1990s, I couldn’t check his story. On the rare occasions when I heard The Wearing of the Green, I thought of the Jamaican’s tall tale.

Years later I watched the Jamaican movie Cool Runnings. Only when the credits rolled, I noticed the Irish surnames, Roche, McLaughlin, Crowe, Morrison, Maloney, Harris. A few years later I watched a documentary on Bob Marley and noted a peculiar Irish lilt in some of the words spoken by the Jamaicans.

When the internet became accessible I researched the Jamaican link and found a few staggering facts. The extent of Irish emigration to the Caribbean and Jamaica was so prolific that a staggering 25 per cent of Jamaican citizens claim Irish ancestry, the second-largest reported ethnic group in Jamaica after African ancestry.

The first Irish emigrants to Jamaica arrived more than 200 years previous to my Jamaican friend’s 1850 ancestors. In 1641, Ireland’s population was 1,466,000 and in 1652, 616,000. According to Sir William Petty, 850,000 were “wasted by the sword, plague, famine, hardship and banishment during the Confederation War 1641-1652.†At the end of the war, vast numbers of Irish men, women and children were forcibly transported by the English government.

In 1655, when England captured Jamaica from Spain, Oliver Cromwell needed to populate their new colony. Some were convicts, many indentured servants and very few of the deportees had committed any great crimes. Deportation “beyond the sea, either within His Majesty’s dominions or elsewhere outside His Majesty’s Dominions†was one of their methods of dealing with the Irish issue and, more importantly, populating England’s new acquisition.

One man whose crime was to harbour a priest was imprisoned, while his three daughters were sent to Jamaica. In order to prevent the new arrivals forming communities the three girls were sent to different corners of Jamaica. Large numbers of the Irish exiles died from heat and diseases.

It was thought that the Irish would have a better chance of survival if they were introduced to the climate at a young age. Cromwell then sent 2,000 children between the age of 10 and 14 years.

Migration to Jamaica continued through the 17th century. The term Redleg was coined. The fair skin of the Irish frazzled beneath the Caribbean sun. The Irish exiles were not chattel slaves. Their white skin meant they would know freedom when their indenturship expired.

Some Irish emigrated willingly, especially during the sugar boom, but few had any of idea of what to expect. In 1841 a Jesuit priest recorded the arrival of a ship from Limerick, “They landed in Kingston wearing their best clothes and temperance medals.†They laid their roots and contributed to Jamaica’s changing island and motto, “Out of many, one people.â€

Some Irish acquired land and slaves. Names like O’Hara and O’Connor were recorded in 1837 during the compensation hearings when slaves were freed and their owners remunerated. The strong Irish influence is seen in place names, Irish Town, Clonmel, Dublin Castle, Sligoville, Belfast, Athenry and Kildare.

Not only are the Irish surnames and townlands evident of the strong shared history, there are striking similarities between the Maroon dance formations in Accompaong and Irish reels.

There are words spoken in remote parts of Jamaica with a clear Irish lilt and there are songs sung reminiscent of the struggles that continued in their homeland while they laid roots in their exotic new home, Jamaica.

My novel, The Tide Between Us (Poolbeg Press), is dedicated to the many Marys, Margarets, Patricks, Seans and the Jamaicans who continue to celebrate their Irish heritage

Olive Collins, The Irish Times.