‘Can you honestly see nothing wrong with the way women of my age are treated?’ Mary Walsh asked this question of An Taoiseach Micheál Martin about The Marriage Bar which prevented married women from working

Until 1973, Irish women were forced to resign from work due to The Marriage Bar, and many women are reminded of it weekly when they collect their reduced pensions. The possibility of rectifying the pension inequality caused by the bar is now the concern of an Oireachtas committee.

Mary Walsh regularly tells her children to never forget how the State aggrieved her.

She tells me this as we sit in the dining room of her home in southwest Kerry. The sun beams through a big window at the end of the room, offering views of her front garden filled with flowers of every sort. “I love flowers,†she tells me, smiling.

The bright, sunny weather and Mary’s warm and friendly disposition are overshadowed by her story of aggrievance, which surfaces strong feelings of hurt for her.

Mary is one of thousands of Irish women who were forced to leave the workforce upon marriage. The Marriage Bar, introduced in Ireland in the 1920s and lifted in 1973, required women to resign once married and disqualified married women from applying for vacancies. Many women affected receive a reduced pension today because they cannot meet the required number of pension contributions.

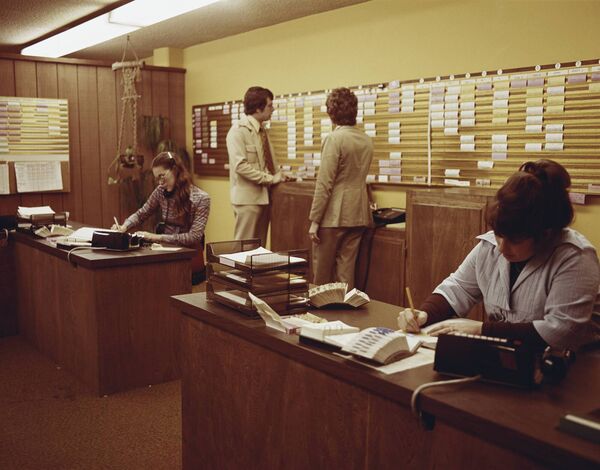

The government first introduced the marriage bar in the civil service as a cost-saving measure, but its practice was widespread across the public and private sectors, reflecting the culture that a woman’s place was at home.

Civil service Â

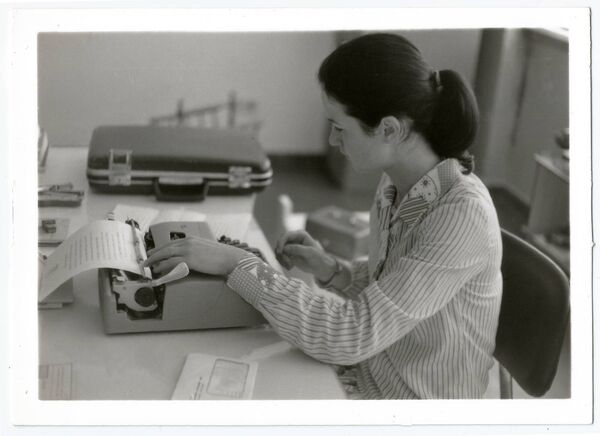

Mary’s working life began in 1967 as a clerical assistant in the Department of Justice. Being the only woman in the office, she recalls how all seven positions above her were held by men, making the modern ambition of climbing the ladder something of a mystery.

“It never dawned on me when I was applying that there would be no male clerical assistants.†Despite this, each time she recalls her civil service years, a smile widens on her face. “I had great camaraderie with my colleagues. I couldn’t fault any of them. I really loved it.†This was the case until 1972 when she got married and was forced to resign.

While the marriage bar was commonplace worldwide, Ireland was one of the last countries to lift it — 20 years later than most. The Institute of Labour Economics estimated that in 2011 up to 57,000 women were not qualifying for a full State pension because of the marriage bar.

Pension inequalityÂ

In many cases, women’s pre-marital working years were seen as worthless when calculating pension entitlements. This was the reality Mary and many others like her faced in 2016 when she reached pension age.

“I wasn’t allowed to take the stamps for the four years in the civil service into account. When I appealed it, I was told those stamps were good for nothing. One officer told me her own mother was in the same situation, and she couldn’t do a thing about it.â€

But it was the 2012 pension changes that hit people like Mary the hardest. Introduced as an austerity measure, the changes made it harder for those without a full-time, long-term working history to qualify for the full contributory State pension of €230-a-week.

Of the 36,000 people who faced these pension cuts, 62% were women, many of whom were affected by the marriage bar, or who had stopped working to raise their children.

For Mary, this meant the years discounted from the civil service, alongside almost 25 years at home caring for her children, left her short €35 in her weekly pension.

In 2018, the government introduced a Home Carer Credit of up to 20 years to remedy this pension inequality. While this was a welcome concession, Mary still faces the marriage bar’s ripple effect despite re-joining the workforce in 1995.

“I worked in the local Credit Union for 18 years, and I was granted 20 years of caring credits. I’m now €15 short of a full weekly pension, but if I got my four years in the civil service, I would have a full pension.

“While €15 doesn’t sound too bad, it’s almost €1,000 a year. Aside from the money, it’s also the worthlessness of my time. The ministers don’t go up in 10s or 20s when they get a rise; they go up in thousands. So, I feel hurt.â€

Taking actionÂ

But Mary has not let her anger fester. As we sit at her dining table beside a neat pile of pension documentation and newspaper cut-outs, she reads me excerpts from emails she sent to various politicians over the years. Including one to Taoiseach Micheál Martin, where she asked:

“Can you honestly put your hand on your heart and see nothing wrong with the way women of my age are treated? I would suggest that you allow us, at the very least, to count in our credits before [the marriage bar was lifted].†In 2017, Mary was part of a delegation of women — led by the National Women’s Council of Ireland — who travelled to the Dáil to lobby politicians on the cause.

“Everybody I met that day understood my story. They were all in favour of sorting it.†But how much progress has been made? Very little, according to Mary.

Successive governments have referenced the issue in the past, such as in the 2010 National Pension Framework, concluding that it could not address shortcomings from social insurance gaps in the past.

In 2017, then Minister for Finance Paschal Donohue told RTÉ that the State could not afford to compensate the women affected, calling it a “bonkers lawâ€.

Sinn Féin spokeswoman on workers’ rights, Louise O’Reilly, believes there is scope for the government to address the issue:

“I think the best place to start would be a meeting with the relevant ministers and the women affected…or an information-gathering exercise to see how many women are implicated.

“I think a case could be made that the women who left because of the bar would have their pension entitlement examined, and for a bit of latitude shown to them purely because their service was forcibly broken by law. These women got sacked for the crime of getting married.â€